It was pretty easy to write this blog entry. Essentially, I just consulted my Workflowy goal list that I've been accumulating. I organize my life around Workflowy, using it as my to-do list, idea capture tool, journal, shopping list, and bucket list of things to do. Everything (thousands of items) goes in one simple and elegant document, but it's super easy to find exactly the information I'm looking for at any given time. Much better than a GoogleDoc. Check it out if you're looking for a productivity tool for the new year.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Why only one goal?

One mistake I made last year was focusing on too many goals at once. I gathered a massive bucket list, pared it down to 3-5 goals per month, and it was still too much. I wanted variety so that I would develop multiple skills and ways of thinking that could synergize, as well as discover new things I was passionate about. That logic still holds- and I still intend on trying a variety of things.

Other than my research, this year I will only focus on one goal, my Major Goal for 2013. Reasons:

1) Spend less time planning, more time doing. Last year I found myself worrying about planning when and for how long I would work on each goal, so I spent more time optimizing my schedule than actually accomplishing anything.

2) Focus and deliberate practice. If something is really worthwhile, then it's worth pushing my limits on it, challenging myself, and taking the time to carefully analyze and optimize every aspect. Rather than just haphazardly grinding through the task so that I can run to my next goal, I will sit and force myself to THINK. What are the essential elements of this goal and which will yield the greatest benefits? How can I continually improve? How can I apply these skills to other activities in an unconventional manner? What mistakes do I make and how do I fix them?

3) Prioritization. Taking the time to identify what is really useful or important will allow me to put less stuff on my to-do list but still get more stuff done. A long, unprioritized to-do list is the best friend of procrastination.

4) Habit for life. Some skills are so invaluable that they ought to be life habits. Yet we often don't do them because we don't prioritize them.

_______________________________________________________________________________

The Goal

So I can TRY many things at once, but I will only be focusing on ONE GOAL. This one fought off quite a few other contenders from my list.

~Goal: Read one book per week~

That's it. Looks simple on the surface. Check back later for a detailed blog post on my Major Goal for 2013. I'm not going to be reading casually- I will actively improve my actual skill of reading (speed, comprehension, control, deep thinking, etc). One book a week is pretty ambitious for me, so I will adjust as necessary.

_______________________________________________________________________________

What else might I want to accomplish?

I love variety, so I'm going to try a bunch of other things. But these won't be "goals" where I need accountability, tracking, and analysis. They fall into two categories:

1) Habits I definitely want to continue. No need to focus on them, as the habit has already been more or less established.

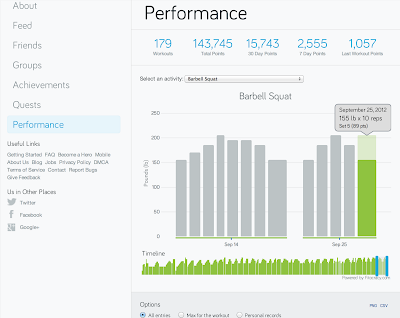

Fitness

Journaling

Blogging

Reading scientific papers daily

Generating ideas daily

Introducing myself to random people in cafes

2) Things I may experiment with this year. I may elevate one of these to a Major Goal for 1-5 months (meaning I focus on it, not just try it), but only if I'm comfortably completing one book per week. Again, truly focusing on a goal is an energy- and time-intensive endeavor, involving a lot of research, experimentation, reflection, and analysis.

Lucid dreaming

Learning Spanish

Writing letters or e-mails to scientists that I find unique and intriguing

Thoroughly organize my lab notes at a set time every day

Carry around a pocket notebook so I can capture all my thoughts and observations

Travel to multiple countries (Asia and South America especially)

Learn 20 tunes on a new instrument

Try snowboarding, rock climbing, and/or parkour

Take a couple of online courses

Develop out-of-the-box teaching methods and make them freely available

Write a program to analyze something in lab or get something done faster

Leadership skills

Conference crashing (completely unrelated to my professional/private interests)

_______________________________________________________________________________

Long-term goals:

Finally, it's a good idea to reflect on what sort of life I want in the future, although my plan is certainly a work-in-progress. Of course, it would be a terrible mistake to fret about whether or not what I'm doing right now will translate towards my vision of my future. This year I learned that "Following your passion" is terrible advice. Instead, I should utilize my current environment to develop long-term skills that can be applied to anything I decide to pursue later.

What I want:

Every single year, I should do at least one big thing where I can say, "Wow, last year I never imagined I would be doing what I am doing right now." Diversity of experiences, both in professional and private life, is most important to me. Career-wise, that means pursuing many different career options, but only one at a time. For example, one decade as a practicing neurologist, one decade focused on basic research, one decade working on startups, one decade part of a large company. At some point, I'd like to be a contestant on Jeopardy!, teach an online course, start my own business, give a TED-esque talk, make a bunch of DIY projects, and go into space. Yes, I'm totally serious about that last one.